It’s been almost exactly two years since the Trump administration placed a 30 percent import tariff on solar cells and modules. And in large part, the industry has coped.

Market conditions like module oversupply and growing corporate appetite for renewables have helped projections for the utility-scale business exceed pre-tariff forecasts. The administration has even logged some manufacturing wins; companies such as LG, Hanwha Q Cells and JinkoSolar have all opened module production facilities in the U.S.

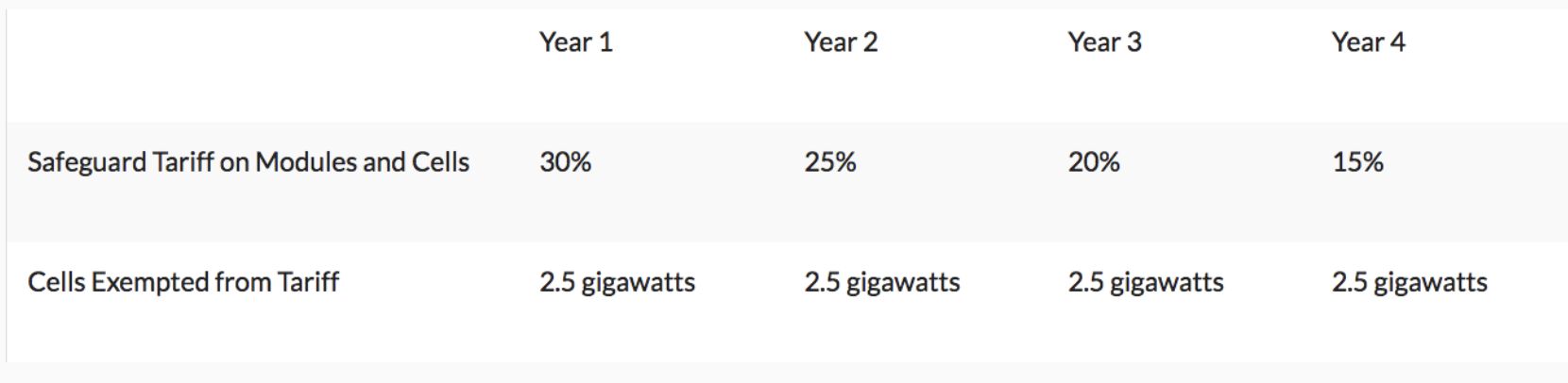

Despite that success, many solar players say companies would be doing even better if they weren’t forced to weather tariffs, including the huge uncertainty that preceded the administration’s actual announcement. Import tariffs started at 30 percent, declining 5 percent each year over a four-year period through 2022.

“Our original position continues — we think the adverse impact of the tariffs far outweigh any benefits,” said John Smirnow, general counsel and vice president of market strategy at the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA).

With the U.S. Trade Representative and the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) currently preparing a midterm review of the Section 201 tariffs’ outcomes, industry voices like SEIA and others have another chance to be heard.

SEIA does not believe the review legally allows for a further strengthening of the tariffs. But the Trump administration could change the stepdown schedule, cancel the tariffs or otherwise modify them.

In addition to examining the tariffs, the trade commission will consider raising the quota placed on exempted solar cell imports — currently 2.5 gigawatts per year — to 4, 5 or 6 gigawatts, which would offer domestic module manufacturers access to more duty-free international supply.

The report is slated to head to the president in early February. Trump will then have indefinite time and “broad authority,” says Smirnow, to consider possible tweaks to the tariffs. More broadly, the administration on Wednesday signed a deal with China designed to ease trade tensions going forward.

Industry argues PV imports could boost domestic production

A decision President Trump made earlier this month concerning tariffs on washing machines may shed some light on how the process for solar will unfold.

After the midterm review of those tariffs, the administration decided to divide the washing machine import quota over four quarters, rather than allowing the quota to be consumed on a first-come, first-serve basis when the annual quota period opens.

In comments submitted in the solar tariffs review, the industry seemed to appreciate the unlikelihood of the administration doing away with tariffs altogether. Comments from domestic producers like Hanwha, Texas-based module manufacturer Mission Solar Energy, SunPower and California-based module manufacturer Auxin Solar actually suggested tariffs are working, yielding economic benefits for domestic manufacturers and multiplying U.S. module production.

But commenters, including that group, also argued for a much higher quota on imported cells to remove constraints on domestic module manufacturing, which in 2019 was projected to exceed 5.6 gigawatts in capacity, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Estimates from Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables put domestic cell production around 600 megawatts.

Korea’s LG, which operates a U.S. module factory in Alabama, argued that “there is no longer any credible dispute” about the need for a higher quota for cells. “The only slight difference in opinion is whether the shortfall is large or very large,” the company wrote in comments submitted to the USITC.

Increasing domestic cell production to meet demand is “entirely unrealistic,” said LG. Many in the industry also suggested there’s little incentive to keep domestically produced cells in the U.S. because international manufacturers can use U.S.-produced cells for modules that can then be imported into the U.S. tariff-free.

Tesla and Panasonic are the only companies currently producing cells domestically and Tesla’s comments also support a 5-gigawatt cell quota because the company “needs and procures CSPV cells on the merchant market” for its solar roof.

Avoiding the worst-case outcome

Though SEIA is also interested in seeing the cell quota increased, the organization prefers a complete elimination of the tariffs.

“That’s our principal ask, is get rid of the tariffs. If you don’t do [that], moderate the tariffs,” said Smirnow. “Moderating the tariffs in the right way would also provide meaningful relief.”

A December analysis from SEIA found that the tariffs cost $19 billion in lost private investment and 62,000 in possible jobs, plus the environmental impact of increased emissions that more solar installations may have negated.

Though the industry has proved resilient — with a record 10.4 gigawatts of utility-scale projects under construction and solar edging out natural gas for expected 2020 capacity additions — the trade group said it’s also been artificially constrained by the import tariffs.

As the mid-term review comes due, the tensions at the heart of the solar tariffs survive — even if the companies that spurred them, for the most part, do not. Section 201 petitioner Suniva, a domestic module manufacturer that’s since shut down production, wants to see the cell quota remain at 2.5 gigawatts and the tariff stepdown shrink — efforts the company said would help it bounce back to produce cells domestically.

A slower stepdown would be the worst-case outcome of the review, according to Smirnow.

“Let’s hope they don’t change the stepdown,” said Smirnow. “That could have a significant adverse impact on the industry and is probably the thing we’re most concerned about right now.”